I still recall when I had to wait till Monday to call the Library of Congress to find out things.

You don't really know what's out there. We see a lot more of it. A cat with a thumb. A fish standing on land. Some weird underwater squiggly giving inspiration to the Flumph.

A few months ago, I wrote an article On the Lie of Colonialism in Dungeons and Dragons. I still believe my core thesis in that post. In the entirety of my experience of gaming, I have never had a group that didn't treat or deal with sentient culture-having creatures in a modern "enlightened" way. They always helped the oppressed. They fight against those with power for the good of the people. Even in evil campaigns, they were concerned about Order against Chaos.

In the real world, there is no objective morality. There's no glowing purple-green force one can syphon that by it nature is inimical to the existence of life. There explicitly is in Dungeons & Dragons. You can see it with magic.

But,

I mean, people overreact right? "Oh, hey, what a miserable take this guy has in an article I didn't read, but will publicly complain about on twitter as a preening gesture for my preferred ingroup!"

But,

I have direct experience of working with several extremely low-income high-risk cultural groups. I spent five years in Alaska working with Yup'ik and Cup'ik native tribes. I have experience working with economically disadvantaged cultures in my local area. And I find it strange to have to say this, but this isn't because of any 'white savior' complex. Frankly, you can't save shit. Like, it is in a very straightforward way, the government using money to directly ease the extinction of a culture. And let me tell you, the destruction of a culture is not pretty.

But,

Maybe

Maybe I haven't been to that edge of the map. Maybe one of monkeys banging away on typewriters that fit into their pocket, knew something that I did not. So I've been looking into it. Partly because I'm working on large semi-historical adventure for a. . . uh. . . a thing. . . that I'm clearly not supposed to be talking about.

But it takes place in the colonial era. My initial weeks of research led me, to a conclusion that seems obvious in hindsight, that if an adventure is literally set in a colonial time, in an area nations were fighting over colonies, you can't avoid having colonization in the adventure.

So, what does this mean? Is the act of pretending to be a wizard who engages in slaying orcs, somehow some kind of dog-whistle racist activity? Well, MyFarog and Racial Holy War are universally derided and maligned for their obvious racism. I've never seen or heard of anyone running one of those racial cleansing simulators, so if role-playing were some front full of people engaging in genocide fantasies, I would expect them to be more popular. I mean, maybe those tables are out there, full of people who live their lives like extras who get killed in an action movie.

But, you know, edge of the map. I went out (and am out) listening to lectures, reading and listening to those who do understand the issues, and people who are not like me. I mean, we are all different. That is to say, we all possess infinite worth, but our externals can be radically different. This is something I've carried inside as a truth, that I hold with a fervor equal to its arbitrariness. I.e. total. Now I'm not done thinking, but it seems pretty obvious from my study that when we engage in entertainment via movies, table-top games, video games, reading, story-telling, we construct tales of overcoming adversity versus the self, other people, nature, supernatural, technology and society.

That is, you can totally pretend to shoot bad guys and that doesn't make you a bad person.

That isn't the end of it.

There are clearly depictions of racial stereotypes in the monster manual c.f. dervishes, hobgoblins, et. al. that represent a bigoted view of culture inherited from the sword and sandal novels of the early and mid-twentieth century. A bigoted view Gygax clearly had, and I know for a fact there were people who did not have that bigoted view in 1970.

And what do you do about a thinking culture's children after your murder their adults for being on your land before you got there?

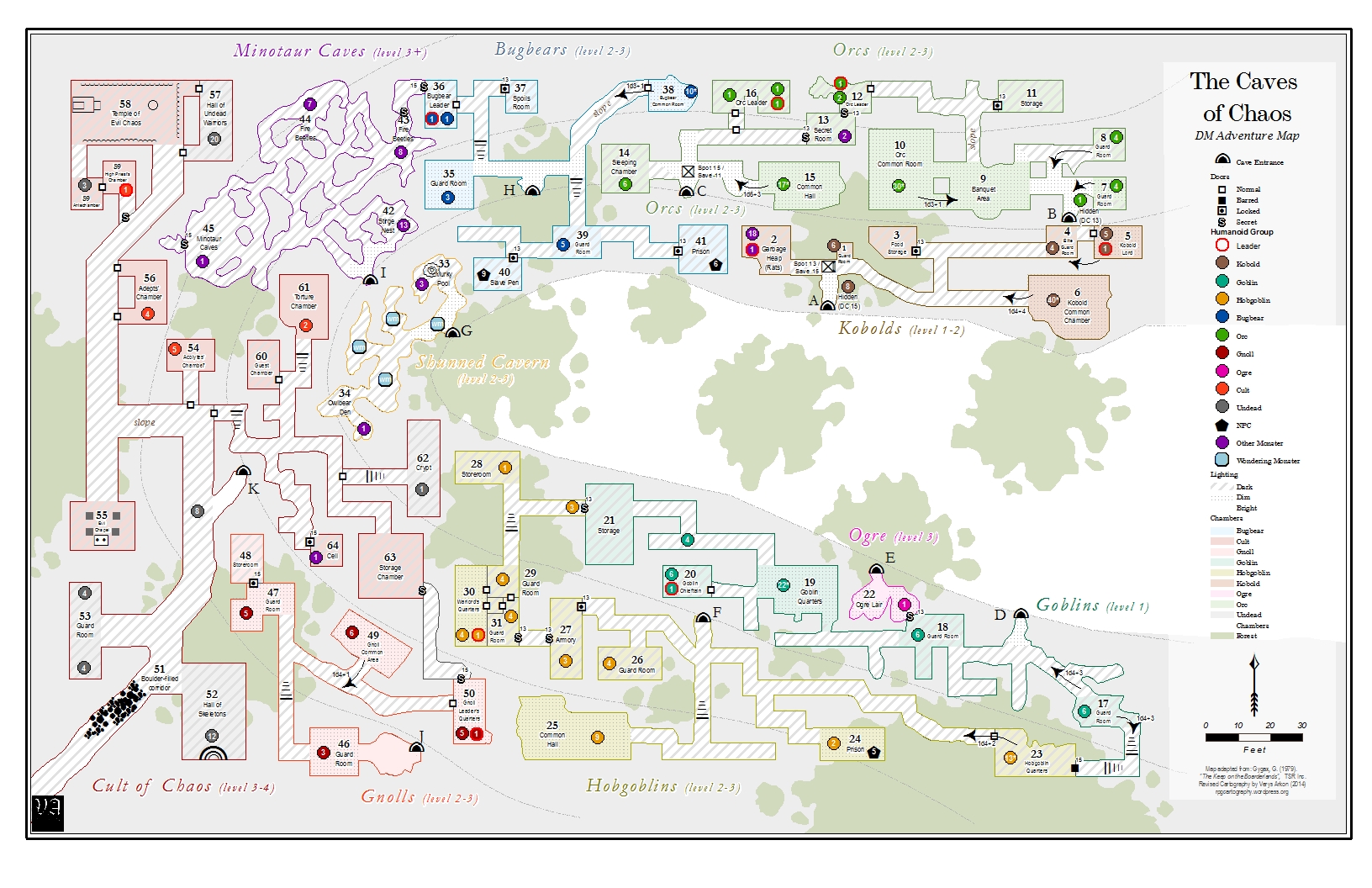

Therein is the rub. You can make the game match cultural understandings and expectations, but you can't stop someone from being a racist douche. So you kind of have to play by some unspoken rules. E.g. You can't have an inhuman enemy that you kill without compunction who has its own culture and values. If they do have a culture, they must have a value that is deleterious to your very existence, which makes it palatable to kill them. Or you've got to expect your players not to want to kill them.

The thing is, and by far, I'm no arbiter of the state of the world.

But I've never seen a game or met a person who doesn't play by these rules. In point of fact, in every game in my entire life I've been involved in, covering these questions has always been done explicitly at the table, to make sure we aren't engaging in some nefarious act.

In fact, it's an ancient trope, being the exact point of U2, The Danger at Dunwater (1982). You are given the location of the lair of the lizard men, but they are just chill dudes, who's really just arming themselves to protect themselves from the cuthonic undersea horrors of the Sahuagin. It's an adventure that literally is about understanding cultural differences to avoid conflict. I've been in and run the adventure an astounding amount of times. Sometimes it takes a fight or two, but there's a 100% rate of 'Oh Geeze, these aren't the bad guys, let's help them defend against the evil, which neither of us could defeat apart', which is a literal parable about why racism is bad.

So has the game "Since its inception in the ‘70s, . . . had profound issues surrounding racism and the colonialist mindset. Fifth Edition has done little to mitigate these issues, and if anything, the West Marches only make the longstanding rot more visible."- Izirion's Enchridiion of the West Marches

I mean, yes. The game has had stereotypical and inappropriate representation. e.g. please do not look at the cover of X8 Drums on Fire Mountain. (I told you not to look.)

Does the game have a colonialist mindset? It's feudal. It has depictions in monsters that have been used to demonify other cultures. Are antibiotics colonial? Spiritually, the core of the game is about going into the chaotic unknown and retrieving knowledge to return to strengthen society and further the cause of order and man.

The argument is, yes. We do so. To take the world and bring it to order, imposes by definition an unjust order. Order itself is a problem. Too much and the world becomes frozen and rigid. I mean, did you see earlier where I used the common colonialist trope of "we are making things better for you." when I mentioned Antibiotics?

You see, while listening and thinking and pouring over tomes, which amazingly enough is my actual job (Made possible by awesome people who give me money! You too can join this exclusive club of raising the volume of a voice you like. Blame capitalism.) It occurred to me that the discussion, and there is a discussion, is about how to respect autonomy, dismantle unjust hierarchies, eliminate unfair exploitation, and make the world a better place.

Which, funnily enough, is exactly what the fuck Dungeons and Dragons is about.

There's no answer to the question. We still remain as a species in the period of unknowing. Maybe there will be an answer to the question of a perfect society one day. Hell, I don't have to wait till Monday morning to call the Library of Congress to find things out anymore. But the game itself is literally about answering the question: what is right, what is just, and what is within my power to improve?

The game itself deals with profound issues. Important ones. Like racism and the colonial mindset. Fifth edition hasn't done anything to mitigate this, it's still about important things, like Freedom and Representation. The game is about personally taking agency and being confronted with this question. It is about what colonialism means and what complicity and rebellion cost. It's about what it means to be a hero. So when I say that colonialism in Dungeons and Dragons is a lie, what I mean is that the idea of our personal exploration of these issues is somehow bigoted or racist is, as the kids say, a bad take.

And I would hope, in my heart of hearts, when you venture into the West Marches, beyond the edge of the map, that the longstanding rot is clear and visible, so your blade may strike true when you fight for justice.

Happy Thanksgiving! I hope this post finds you and yours well. I've very recently solved looming housing insecurity, and it occurred to me no one should have to suffer housing insecurity. If your interested in helping, there are a lot of resources that allow you to help out locally and nationally. We are in for a rough decade—and we can make it through, together. Tell your loved ones you love them.

The whole colonialism issue strikes me as "Satanic Panic-ish" because where are the people sacrificing these children? Is this something that is really happening, or is it a reaction to the ambiguity of what other people might do 'wrong' while playing a game? I don't think so, but don't know for sure. It seems somewhat self-selecting, racists are almost by definition provincial, and role-playing does require a lot of traits that are contraindicated to someone who has racist beliefs. What's the angle on targeting it? I'm not sure. But there's a definite disconnect between the claims and the reality. What, exactly do we do about racism? Forty years of anti-racist propaganda and societal efforts, and. . . nothing. Still Racism. It might be, I think, related to genetic in-group/out-group stuff and I don't know how we get rid of that. I don't have to know to play D&D.

If you're curious, I'll put the old article up Friday and you can read it then.

If you're interested in something cool, I have some crazy art in this adventure about a dungeon inside a dead sea god. There's other factions and goals, it's a really smart adventure. So much cool stuff and my art, too! Take a look at Voyages on the Zontani Sea!

And, oh, it's so crazy. Dungeons and Dragons is so crazy popular, JeShields who's both a technical and spiritual mentor of mine creates crazy high quality art. It's so good. Someone like it so much, they are turning the art into 3-d miniatures? It's just awesome. I think everyone should go have a look. Just to see how cool it is to take a 2D old school type illustration and turn it into a monster.